Interested in Onsite Systems?

Get Onsite Systems articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Onsite Systems + Get AlertsLocated in the remote Arrowhead region of Minnesota – between Lake Superior and Canada – Cook County has only 5,000 people. Most of the forested land is government-owned, so land available for development is expensive. A growing segment of the population enjoys an alternative lifestyle, and these people are looking for better ways to handle their wastewater on a tight budget.

That includes those who live in very small rustic homes without electricity or running water. Some are called yurts, which are becoming popular with “off-the-grid” residents. A yurt is a fabric home of 100 to several hundred square feet built on a wood base with a wood frame and rafters, lattice walls, and framed doors and windows. While popular as vacation cabins, they are also used as year-round homes by some because they are so cheap; a 700-square-foot yurt may cost around $10,000.

Thanks to a board of county commissioners willing to listen and a health officer with some imagination, the people got what they wanted. Commissioner Heidi Doo-Kirk, a self-employed bookkeeper with a background in septic system design, broached the topic of allowing alternative systems as the county was rewriting its septic ordinance in 2013. She used to work for S.J. Bautch Construction in Grand Marais, Minnesota, where she earned certification in septic system installation and design.

The new ordinance allows “privies, seasonal porta-potties, incineration toilets, seasonal and year-round composting toilets.” But Mitchell Everson, county environmental health officer, also designed systems for low-flow households that gained the support of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency for use outside shoreland areas.

Everson developed two graywater systems for hand-carried water and pressurized systems, and another to handle toilet waste. The mini M-box and M-box are designed for primitive dwellings with flows of around 30, 108 and 180 gallons per day. Patent applications for the systems have been filed.

Pumper: What are some of the design standards for these systems?

Everson: The mini M-box is a 30 gpd graywater gravity system for hand-carried water. Most people at our meetings said they use 3 gallons a day or less. By law, you can hand-carry it back out and distribute it on the ground, but if you put it into a pipe, you need a treatment system. Most just have a washbowl inside, so we added a strainer to capture the food bits and scraps and clean-outs in the pipe. The pipe leads to an insulated bottomless box that is 8 feet by 4 feet and 4 feet deep. The box must have at least 2 feet of vertical separation (washed sand in most cases), rock distribution media, and 12 to 18 inches of sandy loam cover. A homeowner can build the box and install the system for around $1,000.

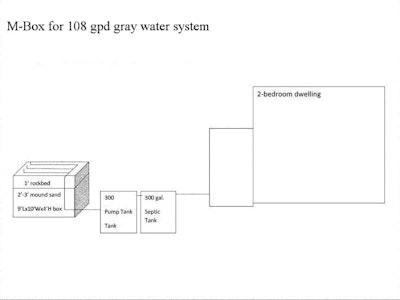

The pressurized M-box is a 108 gpd graywater system, a small version of a mound that is 9 feet long by 10 feet wide and 4 feet high, with 2 to 3 feet of sand, rock distribution media and a sandy loam cap. There is no pretreatment like you would have with a typical box mound. It can be built by hand or with a mini excavator for about $4,200.

For a pressurized water system for graywater or toilet waste, the M-box also has a 750-gallon septic tank and a mound system that is 15 feet long by 10 feet wide and 4 feet high with a 300-gallon pump tank. A 180 gpd system can be built for around $5,000 to $7,500. The septic tank has to be maintained like all other systems; it should be assessed for pumping every three years.

A homeowner can come in with similar designs. We’re interested in accommodating them so they can install something that fits their needs for these primitive dwellings and still protect public health and the environment.

Pumper: Heidi, how did your background in septic design help in this project?

Doo-Kirk: When I was elected to our county commission, the state had asked us to update our septic ordinance and, with my background, I volunteered to sit on the committee. We have a tough time up here. We’re pretty much stuck with mound systems that cost $25,000 to $40,000.

The government owns 92 percent of the land in Cook County, so property around here is expensive. With land and septic, you have $100,000 invested before you even have a house.

A lot of people here live off the land and want to build their own homes with graywater systems. It is legal to just throw it outside, but it’s not OK to put it through pipe. A lot of them have gardens, so one day I asked why we couldn’t have a system for them that works like a mound system and filters the graywater. I drew up a small box with all the same characteristics of a mound system and asked if we couldn’t use that. Mitch looked at me a little strange, went into his office and designed it, and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (PCA) accepted it.

Everson: I had already come up with the M-box for the pressurized graywater. And then the discussion went to the hand-carried water and the people who wanted it to go out a pipe. So from that discussion, I did more designs to show that it could be done and confirmed that with the PCA.

Pumper: Were you surprised that the PCA accepted it so easily?

Doo-Kirk: They were great. They Skyped into some of our meetings and came to a couple. Now we have a few other counties contacting us trying to figure out how they can do it elsewhere in the state.

Everson: When PCA announced that counties had to update their ordinances, they brought up the idea of alternative local standards if we wanted to pursue them. This is far better than people just taking their graywater and surface-applying it, so why wouldn’t they go for it?

Pumper: How many yurts are there in Cook County?

Doo-Kirk: I know of at least four, but they don’t need a land use permit so we aren’t sure. We have a lot of water and people are worried about protecting it. We had about 70 people show up for the public meetings on the new septic regulations.

Everson: There seems to be a growing community that wants to live that low-impact lifestyle. There are quite a few who come through the office and want to know what’s available and what alternative systems they can look into.

Pumper: How many of these systems have been installed?

Everson: The ordinance was approved just last spring, and we approved one last fall that hasn’t been installed yet. Once one goes in, the word is going to get around. Once people see and understand that there are alternatives, we’re going to see a lot more of this happening. I think it will be a hit.