Interested in Portable Sanitation?

Get Portable Sanitation articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Portable Sanitation + Get AlertsIf you have visited the nation’s capital, there is a sight you may not have expected to see while touring monuments, government buildings and museums. Look in the right places at the right times, and you see homeless people trying to stay alive under highway bridges and in public parks. In addition to having no shelter, these people face another problem: lack of proper sanitation.

It is an issue that directly affects portable restroom operators in the region around Washington, D.C. They pay a measurable price for the lack of a solution to part of the homeless problem. But a nongovernmental organization is pushing for a solution that would indirectly help pumping companies while directly helping the homeless.

THE HOMELESS TALLY

The number of homeless in Greater Washington, D.C., would populate a small city. In their January 2016 shelter count, Washington-area governments found 12,215 homeless people.

Every year, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments prepares a report on homelessness in the four Maryland counties, three Virginia counties, and city of Alexandria, Virginia, that comprise the metropolitan region along with the District of Columbia. The most recent report determined homelessness rose by 3.3 percent from 2012 to 2016. Although homelessness dropped in some places — the extreme was 61 percent in Arlington County, Virginia — it increased steeply in two places: the District of Columbia (20 percent) and Frederick County, Maryland (22 percent).

And although the stereotype of a homeless person is of a single middle-aged man, that is mostly not the case. In its January 2015 count, Fairfax County, Virginia, found 54 percent of homeless people were in families.

AN INDUSTRY ISSUE

Portable sanitation companies are very much a part of this issue because of the service they provide. Fred Hill is co-owner of Gotta Go Now in the District of Columbia, and he can instantly pinpoint the lost revenue homelessness cost his company in 2015: $12,800. The figure was calculated based on dirty or damaged units that had to be replaced or because use by homeless people had denied access to clients.

“In the wintertime, homeless people take over portable restrooms for shelter. We’ve seen units locked from the inside, and when we forced the door open there’s a mattress on top of the toilet and a person on top of the mattress,” Hill says.

If his technicians padlock the door of a unit left in place between events, people angry about being denied access may flip the restroom over. That requires an additional trip to bring out a fresh unit and take the flipped one back to the shop for a thorough cleaning and sanitizing, Hill says. “And no one pays for that work.”

Reached on a Monday, Hill explained that Gotta Go Now had just finished with a weekend event that required 20 units to serve about 1,000 people. Technicians serviced the units throughout the event, but it was late Sunday night when the event ended, so units weren’t picked up until Monday morning. When technicians arrived, the units were full.

Although National Park Service rules require removal of units within 24 hours of the end of an event on land it controls, such as the Washington Monument grounds, area communities sometimes want units left in place throughout the week so they’re on site for the next weekend event, Hill says.

“I have suggested to local officials that these units should be monitored daily. It would minimize damage and improve cleanliness. When you think about it, it makes no sense that people send a janitorial firm into an office building every night to service its toilets yet request only weekly service for a portable restroom.”

SEEKING A PERMANENT SOLUTION

The People for Fairness Coalition is thinking along the same lines. The local nonprofit group is composed of homeless and formerly homeless people advocating for themselves, and part of the group’s mission of caring for the homeless is providing them with acceptable sanitation. As is clear from Hill’s experience, this is no easy task.

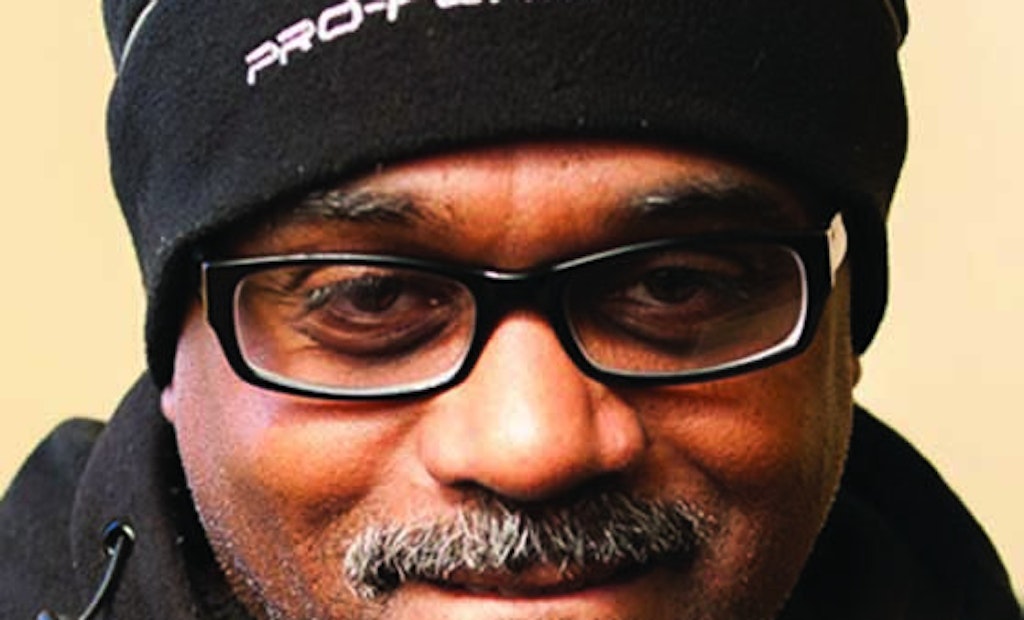

“Just about every building is monitored,” says Albert Townsend, who helped organize the coalition. “Since 9/11, every public building is secured by guards.” That means contracted private guards or police from the Federal Protective Service that secures federal facilities.

There is a public restroom in front of the Washington Monument, but it is not open at all times. Portable restrooms are available only when there is an event. At any museum, people must check in and go through a security process before entering the building. “That really discourages people in the homeless community from going into any public space,” Townsend explains.

The downtown District of Columbia homeless population is approximately 700 people, the smallest cluster in the area, Townsend says. Most homeless are outside the center of the district and congregate where they can find necessities such as food, clothing and health care.

The coalition’s goal is a permanent restroom that would be regularly cleaned and monitored, would be open 24 hours a day, and would be located in one of the district’s neighborhoods. It’s a model already used in Seattle and Rhode Island.

This would require more money up front compared to placing a series of portable restrooms in areas of need, but it will be a better long-term solution, Townsend says.

HELPING BUSINESS, THE HOMELESS

Such a building would be constructed to accommodate bicycles and the belongings of homeless people who now must leave their few possessions unattended while they use a restroom. Stalls would be open along the bottom so someone could see whether or how many people were present. And people in the neighborhood around the permanent restroom could be employed to clean and watch the facility.

Every December, the People for Fairness Coalition holds a vigil to commemorate the lives of people who live and die on the streets of the nation’s capital. People who deal with the homeless see the clear value of a permanent restroom facility for them, Townsend says. Hill sees the need and the value.

“I’m open to talk with the coalition. From the industry side maybe there’s something I can help them understand,” Hill says.

The question is whether metropolitan leaders can assemble the political and financial support to do what would be good for business and good for people.