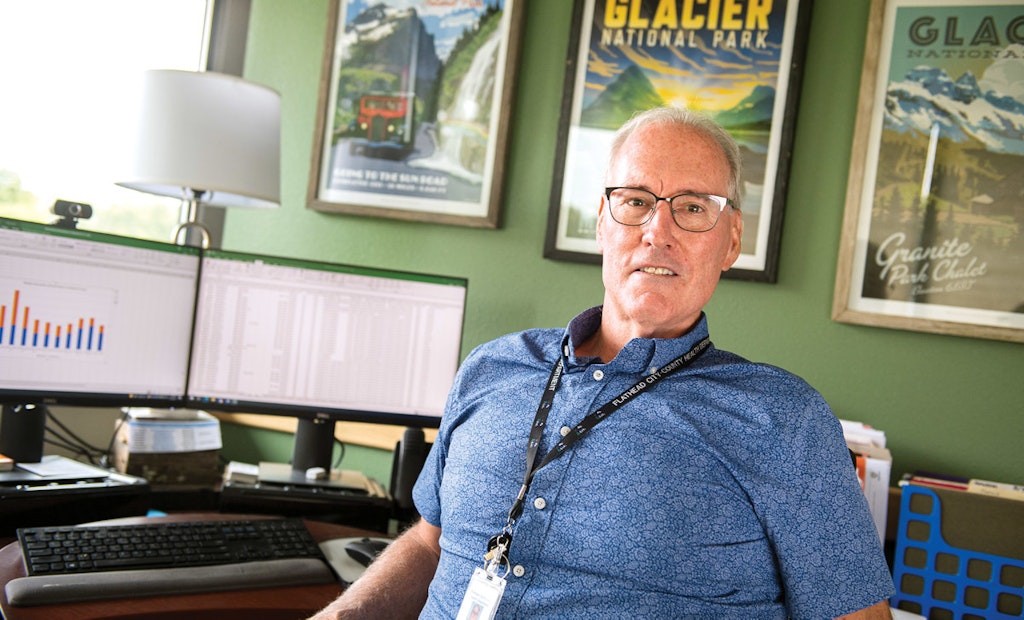

Joe Russell has been a sanitarian since 1987 and for 20 years ran the Health Department in Flathead County, Montana, as the health officer. He retired once, but he’s back in his old job for a while because of difficulty finding his replacement. Yet he now has the opportunity to...

No Place To Dump? Montana County Plans New Septage Dewatering Facility

In a popular tourist area, officials plan to use American Rescue Plan Act funds to help solve local disposal issues.

Popular Stories

Discussion

Comments on this site are submitted by users and are not endorsed by nor do they reflect the views or opinions of COLE Publishing, Inc. Comments are moderated before being posted.