Interested in Onsite Systems?

Get Onsite Systems articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Onsite Systems + Get AlertsIn March 2021, the Illinois River Watershed Partnership launched a septic remediation program to help applicants pay for system upgrades or replacements.

“It’s a unique program. It’s a pilot. It’s the first of its kind in the state. And it’s being designed, roughly, around a program that’s been very successful in Missouri,” says Matt Taylor, program manager for the Septic Tank Remediation Program at the partnership.

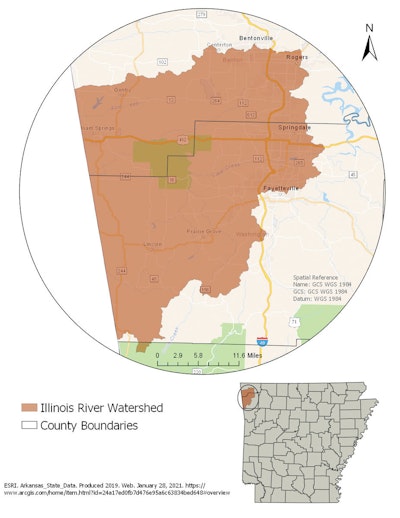

The program covers about half of the watershed for the Illinois River, about 1,650 square miles, which starts in northwestern Arkansas near the urban area covered by Bentonville, Rogers, Springdale and Fayetteville. Then it flows west into Oklahoma, turns south, and eventually joins the Arkansas River as it flows back east to join the Mississippi.

Water quality in the river has been a concern for years, Taylor says. “You’ve got just ever-increasing urban runoff.” That and agricultural runoff are the biggest non-point pollution issues, he says.

Through its reporting of impaired waters under the U.S. Clean Water Act, Taylor says, the state found that failing septic systems were a likely contributor to the problem. “The impairments that we see in our watershed are pathogenic indicator bacteria, nutrients, sulfates and chlorides, which are all associated with wastewater effluent,” he says. Other waterways are impaired by phosphorus.

PROJECT FUNDING

Money for the program comes from the Arkansas Department of Agriculture through a Clean Water State Revolving Fund grant. Normally this grant funding is available to a government entity or utility for a single large project, Taylor says. In this case it comes to the partnership, which distributes money to homeowners for septic projects.

State money sent to the partnership is a grant, so the partnership does not need to repay it. But a portion of the money paid to homeowners is a loan. Repaid loan money goes into a special account that will fund more septic remediations after the grant period has ended, he says.

How much of each project becomes a loan depends on the homeowner’s income. People at the highest income level may receive only zero-interest loans. As homeowner income decreases, the zero-interest loan amount is lower, and the rest of the cost of a system remediation is given as a grant.

At the lowest income tier, the homeowner is still responsible for a loan equal to 10% of the project cost.

The maximum reimbursement allowed is $30,000. That was based on the Missouri experience, Taylor says, and is so high in case a property requires a high-end advanced treatment unit.

“But by and large, and certainly what we’ve seen so far pretty early on in the program, our projects are expected to fall well within that cap,” Taylor says.

And it is a reimbursement, he stresses. The partnership does not pay any money until the final invoice is issued, so a homeowner may have an initial outlay for design services or other work. So far, he says, no client has been unable to afford a project. And, he adds, some installers have enough cash flow to issue credit for a few weeks until money comes through from the state.

MOSTLY CONVENTIONAL

In this area of northwestern Arkansas, high groundwater is often an issue, Taylor says. And the underlying geology is karst with bedrock that is typically limestone and dolomite. “So you have some open groundwater pathways.”

It may look like a recipe for advanced treatment units, but Taylor says no. “All of that said, the majority of systems we have seen in the area are conventional gravity systems that are just very carefully placed.”

The soil profile is quite varied. Geologically speaking, the area is on the Ozark plateau shaped by rivers, which can produce a wide variety of soil types, everything from sandy loam to clay, he says.

Taylor came to the program after a career in health care administration. He owned a pharmacy for 16 years and worked for a hospital system for four years.

All along, he worked as a volunteer with various conservation organizations and has always been an outdoor enthusiast. “And I decided to make a stab at making that my career,” Taylor says. “A few years ago I made the decision to change careers, went back to school and pursued an environmental science degree.”

He came to the partnership after working for Walmart’s environmental compliance division. There he looked at wastewater reclamation technologies, much like onsite septic systems but on a commercial scale, he says.

EDUCATION IS KEY

“I’ve really been struck, so far, by the number of homeowners we interact with who don’t have a proper understanding of how to care for a septic system,” he says. “It’s certainly not their fault. They just haven’t received that education, or received it in such a way that they retained it.”

As a result, the partnership has made a priority of providing educational information, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency SepticSmart materials, devoting some of its website to the topic, and working to put educational material in the hands of area real estate agents.

Taylor says most of the work done so far had been system replacements.

“For the most part, the problems we’re finding are on older systems, and in some cases substandard systems, that were installed at a time prior to any permitting or inspection requirement,” he says.

One benefit of the program that the state Health Department is particularly encouraged by, he says, is finding problems that people may not report on their own. They don’t because they fear they may be cited for violations or don’t have money for repairs.

Previously, most problem systems were identified from complaints by neighbors. As the program started, Taylor says, most referrals came from pumpers, system designers and plumbers.

On the other side of the Bentonville-Fayetteville metro area, Ozark Water Watch is managing a sister program for the Beaver Reservoir watershed. The success of these two programs will help determine if similar initiatives will be considered in other watersheds in the future.

Anyone who sees a problem or has a client worried about costs should know there is help available, Taylor says.