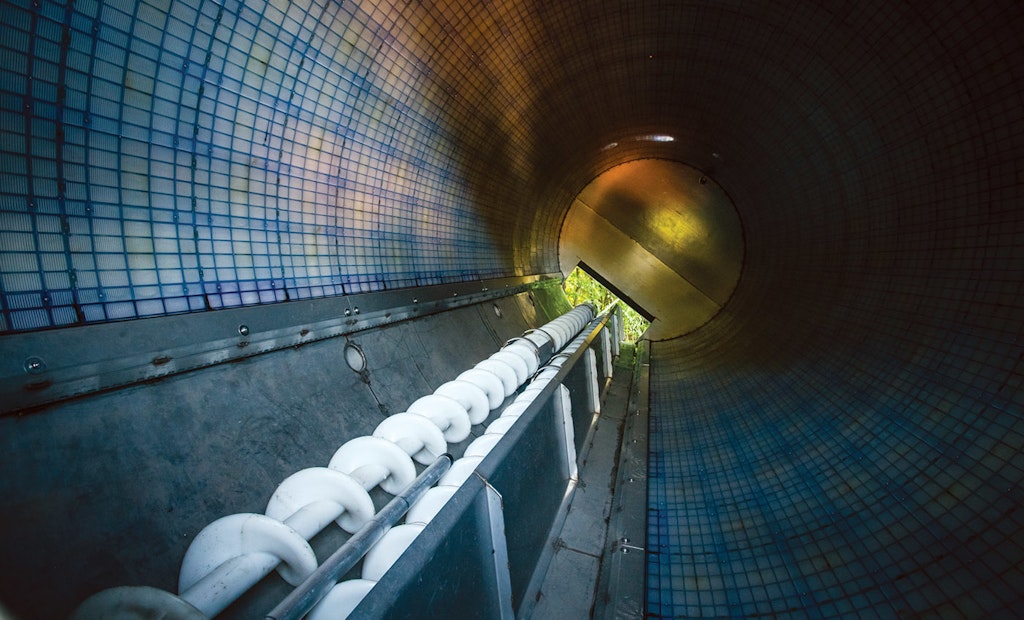

This is a view inside the In The Round Dewatering drum used to process wastewater by Greenway Waste Solutions.

Investing in new trucks and advanced technology is an important part of the blueprint for growth at Greenway Waste Solutions, a fledgling septic and grease trap pumping company based in Charlotte, North Carolina. But in an industry where everyone uses similar equipment, executing the basic principles of customer service provides a competitive edge, says Reese Blackwell, co-owner.

“This industry has become more of a commoditized business, so we strive to differentiate on the customer service component — make things as easy as possible for customers,” explains Blackwell, who owns the company with Scott Simmons. (The Griffin Brothers Cos. also owns a stake in the company.)

“One of the main things we do is just focus on answering the phones and calling people back,” he says. “And we also focus on being consistent. Do what we say we’re going to do, and do it when we say we’re going to do it.

“I know it all sounds mundane … but customer service can be very complex, especially in service industries,” Simmons says. “It takes a lot of effort to keep lines of communication open with customers, but we feel it gives us a little more of a competitive edge.”

A growing fleet of trucks and a soon-to-be-operational grease dewatering system, manufactured by In The Round Dewatering, also has the young company poised for growth. Barely a year old, Greenway currently runs two vacuum trucks for collecting grease and septage. And a third truck is scheduled for delivery later this year, reflecting rapid growth since the company’s inception in August 2018.

The dewatering system is a critical component, especially because the city of Charlotte treatment facilities do not accept grease trap waste. That forces the company to rely on competitors with dewatering systems for grease disposal until its new unit comes online, he says.

When online, the dewatering unit will benefit the company’s bottom line through lower transportation- and disposal-related costs, savings that can be passed on to customers. Plus, the end product, a cakelike mixture will be composted at a Griffin Brothers facility in Kershaw, South Carolina, and sold as an organic yard-and-garden nutrient, Blackwell notes.

“If we weren’t building our own (dewatering) facility, I don’t think we’d get into grease trap cleaning,” Simmons says. “We often pull up at competitors’ facilities and are told, ‘Sorry we’re already full today.’ That leaves us with no way to dispose of the waste, so controlling the waste stream makes way more sense.”

AN EXPERIENCED TEAM

Blackwell and Simmons bring different skill sets to the business. Armed with a degree in business administration from Presbyterian College and a Master of Business Administration degree from the University of Virginia, Blackwell — who previously worked in finance and public affairs — handles business development. Simmons has 18 years’ grease trap and septic tank pumping experience elsewhere. He leads the operational end of the business and also serves on the board of directors for the North Carolina Septic Tank Association.

Simmons was looking for a position in the wastewater industry. Around the same time, Blackwell, who already knew Mike Griffin at Griffin Brothers, wanted a job where he felt like more than just a cog in a wheel.

“I want to get into something more entrepreneurial, a place where I could make an impact every day,” he says.

At the same time, Griffin was looking to invest in a “dirty business,” which he believed had growth opportunities. When acquiring an existing business turned out to be more expensive than expected, Griffin proposed a startup. With a seasoned veteran like Simmons aboard, Blackwell agreed to give it a shot.

The company first focused on septic tank pumping, a market that proved easier to enter while also providing cash flow for the fledgling enterprise. “Initially, our goal was to be a grease trap cleaning company,” Blackwell explains. “But without a lot of experience, selling was hard right out of the gate. … We found that acquiring septic customers was easier because it’s a one-off transaction, unlike restaurants, which want established relationships for recurring service.

“We used Scott’s and Mike’s network to get referrals for septic work, then got more into grease as we went along,” he adds. “It was a slow building process. … You need a significant number of restaurants as customers to fill a (vacuum) truck every day.”

The strategy worked. Today, grease trap cleaning generates about 75% of the firm’s revenue, with septic pumping contributing the balance, Blackwell says.

A SOLID FLEET

To serve both septic and grease trap customers (mostly restaurants), the company relies on three trucks: a 2020 Peterbilt 567, 2018 Western Star 4700 and a 2019 Peterbilt 567. Advance Pump & Equipment outfitted all three trucks with a 4,000-gallon waste and 300-gallon freshwater aluminum tank, vacuum pump made by National Vacuum Equipment (500 cfm) and water jetter made by Cat Pumps (16 gpm at 2,500 psi). Technicians use the jetter, which features 300 feet of 1/2-inch-diameter hose, to clean things like inlet and outlet tees in septic tanks, drainlines and grease trap walls and drainlines, Blackwell says.

The jetting tool is a great value-added feature because it makes the trucks more versatile. Moreover, if a route driver runs into a problem that requires a jetter, the customer doesn’t have to wait for either a plumber to arrive or a Greenway technician to go back to the shop to get a jetter. This boosts customer satisfaction, Blackwell says.

“I wouldn’t even buy a truck without a jetter,” he says. “Sometimes grease is super thick and you have to use the jetter tool to break through. It saves so much time that it pays for itself. Sometimes we get to a restaurant and find the lines are now backing up, and without the jetter, we’d have to go back to the shop and get one. If it’s a long distance away, that’s a profit killer.

“Plus, we can add the jetting service onto the pumping bill … because we’re already there with a truck that can do everything,” he says. “We can cut the customer a substantial deal rather than having them go hire a plumber.”

Greenway opted for aluminum tanks to maximize the carrying capacity; the trucks feature a tandem axle and a drop axle. Each truck is equipped with a digital liquid-level indicator; its accuracy provides a big benefit because the driver doesn’t have to guess if there’s enough capacity left to handle a pumping job.

“If you just use sight bubbles, the tank might be carrying 1,000 gallons, 1,500 gallons or something in between,” Blackwell explains. “It’s one of those little features that gets taken for granted.”

In addition, the technology enables drivers to spot discrepancies between the reading on the truck gauge and a municipal treatment center’s weight measurement, he adds.

HAPPY WORKFORCE

As most pumpers can attest, recruiting new employees and keeping them on board for the long haul isn’t easy. To combat turnover, Greenway pays competitively and strives to treat employees the way they’d like to be treated. The company also invests in newer trucks, repairs trucks quickly and keeps them well maintained, which drivers appreciate.

“We don’t want our drivers burdened with issues for days or weeks,” Blackwell says.

Efficient routing also comes into play as an under-the-radar retention tool. To that end, the company uses ServiceCore route optimization software designed for the pumping industry.

“Proper routing is important,” he explains. “We don’t want to give our guys too many service calls. That makes them run late, and then customers get mad at them. If a driver is supposed to be at a restaurant by 11 a.m., for example, but doesn’t get there until noon, now the restaurant owner is mad because the place is going to smell during the lunch-hour rush.”

Blackwell also notes that the company gives drivers the discretion to change their routes to best accommodate customers’ needs. “For commercial work, our drivers have to be more cognizant of their surroundings — it takes some thinking on their part,” he says. “We need to have faith in them because they’ve been at these accounts before, so they know the customers better than we do.”

POISED FOR GROWTH

So far, Blackwell says management is excited by the company’s initial success, especially bringing in three trucks in 2019. “We’re thrilled about that — over the moon. It would be nice to add one truck every year,” Blackwell says.

Looking ahead, Blackwell anticipates further growth. The real trick, however, is expanding the business while maintaining a high level of customer service.

“We obviously don’t want to grow so quickly that our quality of service drops,” he says. “But our goal is to keep pushing forward. After our dewatering facility opens, it’ll help with cash flow, which will allow us to reinvest more in the business.”

In addition, Blackwell doesn’t rule out adding more services, noting that “solutions” in the company’s name is tailor-made to accommodate such additions. “It was designed to be all-encompassing so we can offer more services in the future,” he says.

Dewatering drum basics

If the pump trucks are the backbone of Greenway Waste Solutions’ services, then its dewatering system, designed to turn grease into a compostable product, is its beating heart.

While Reese Blackwell, co-owner of the Charlotte, North Carolina-based company, declined to give a specific number, he says the dewatering facility represents an investment of more than $500,000. That’s significant, but realistically the company had no choice. Why? The city of Charlotte’s treatment plant does not accept grease. So to dispose of its waste, Greenway has to pay competitors that own dewatering facilities, Blackwell says.

The company could have taken a less-expensive route and employed dewatering boxes. But based on research performed by Scott Simmons, a liquid-waste veteran and co-owner of the company, the business opted to buy a system made by In The Round Dewatering.

“It gets more water out of the cake,” Blackwell explains. “That allows us to carry more cake per load to the composting facility, which isn’t on site (it’s located in Kershaw, South Carolina, about 70 miles from Charlotte). The In The Round Dewatering system also has an auger to remove the cake mix, rather than using a roll-off truck to pick it up and tilt it, so it’s more efficient and cost effective, too.”

In summary, here’s how the dewatering process works: The waste gets run through a screener that separates large trash, then through a grit chamber that filters out sand and grit. Both screening units are made by ScreencO Systems.

From there, the waste first drops into a 10,000-gallon in-ground tank, then is pumped into one of four 20,000-gallon tanks from Dragon Products. When a tank is full, the waste gets mixed with lime, then goes through a polymer-injection process that raises the pH level and helps separate the grease from the liquids.

Then the solution is pumped into the In The Round Dewatering drum through a 3-inch-diameter quick camlock. The drum is made from stainless steel, measures 20 feet long by 90 inches in diameter and is mounted on a roll-off frame.

The drum is lined with interlocking, self-cleaning and replaceable plastic filter tiles. Powered by a 1/4 hp motor connected to a heavy-duty drive chain, the drum slowly rotates on roller bearings, typically one revolution every two hours or so. As the drum rotates, the weight of the sludge gradually presses water through the filter tiles; from there, the water is gravity-fed into a sewer drain.

“Essentially, the water comes out the bottom and the grease stays in the drum,” Blackwell explains. Then the dried cake is augured out onto a concrete pad, where a front-end loader is used to fill a container for transport to the composting facility.

The drum will be housed inside a 3,000-square-foot building located on an acre of property in Charlotte. It’s capable of processing 20,000 to 40,000 gallons of waste per day and should require just one person to operate it, Blackwell says.

“We’re working with an engineer to figure out the most efficient way to operate it with one person,” he says. “Some companies run it all night; we’ll see how it works out.”

The company hopes to also generate revenue by processing grease trap waste for other contractors, as well as by selling the cake as a compost to landscapers and big-box home-and-garden centers.

“Doing our own dewatering will also help us be more competitive in pricing,” he adds. “We can pass the savings on to our customers.”