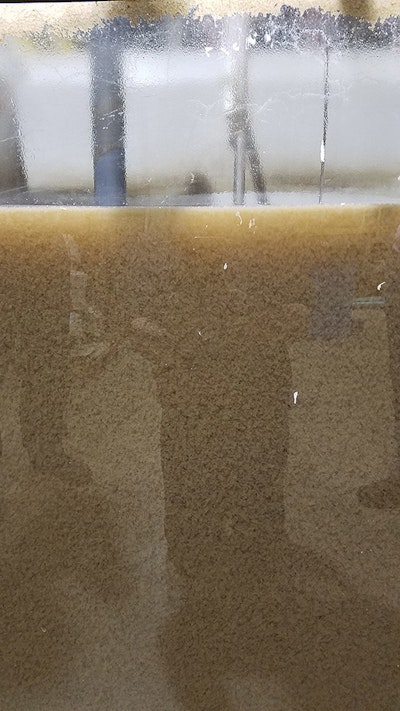

A membrane bioreactor donated by BioMicrobics sits ready for use in the Environmental Resources Training Center at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. The bioreactor is the latest addition to the center, which provides training for new and licensed wastewater operators. (Photos courtesy Rick Lallish, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, and Ray Tebo, NET Excavation)

Advances in wastewater technology help customers and help the environment, but advances can come with a challenge for installers: finding people with the training to handle advanced technology. Rick Lallish saw this problem, too, but from another angle. Through a chance meeting he also found a solution.

Lallish works at the Environmental Resources Training Center at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. As program director of water pollution control, he is in charge of training people who operate wastewater and water filtration systems. He also says membrane bioreactors are poised to be one of the next big steps in wastewater technology.

“We wanted to get in on the ground with this new technology,” he says.

The chance meeting happened at the Illinois Association of Water Pollution Control Operators conference in 2017. Lallish met Kurt Bihler, BioMicrobics distributor, and Ray Tebo, installer. As they talked about what the ERTC does, Lallish expressed a desire to add an MBR to the training facility. After the meeting, Bihler and Tebo, who owns NET Excavation in St. Anne, facilitated connections with BioMicrobics, and the company donated an MBR to the center.

Expanding technology

Lallish says MBRs are becoming more prominent in municipal wastewater treatment. In La Salle, for example, an MBR is part of the treatment chain in the city’s 1 mgd Eastside Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Then there are onsite installations. Tebo regularly uses MBRs in the systems he installs, and all of Illinois currently has about 150 in the field.

“It’s difficult to find the people who can run these units. We’ve had large struggles with that,” Tebo says. “It’s a totally separate business from traditional installing. I have my own shop, my own equipment and my own set of guys who work only on MBRs.”

People who want to run MBRs really need to take the operator course at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, he says. For an entry-level operator, the course is 1,450 hours of instruction that covers the necessary math and science, instrument repair, laboratory work, maintenance and operations. The ERTC is the state’s designated location for continuing education and for training new people. It also trains plumbers in controlling cross connections and preventing backflow.

Illinois isn’t the only source of students at the ERTC. Edwardsville is only 25 miles from St. Louis, and as a result, Missouri also sends people for training. And from every graduating class, two or three students are hired by wastewater systems in metropolitan St. Louis, Lallish says.

Learning by doing

The ERTC trains hands-on with its own wastewater equipment. Lallish holds a Class I license in Illinois and spent about 15 years working in municipal wastewater treatment before moving to Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. There he not only teaches, but also runs the 0.6 mgd activated sludge plant that serves the university’s main campus.

Influent from the campus feeds not only the activated sludge plant, but also a small moving bed bioreactor and now the new MBR.

The MBR has all the parts you would expect, but it doesn’t look like the usual unit. The tank holding the reactor was built by Scienco/FAST - a division of BioMicrobics Inc., and one side has a clear plexiglass window so students at the ERTC can watch what is happening as the reactor runs.

In October 2017, the MBR arrived, and in January 2018, installation was complete and it began operating.

Industry benefit

This partnership between the ERTC and installers like Tebo has a double payoff. First is the ability of university staff to gather data independent of any perceived agenda. MBRs produce very clean effluent, Tebo says, so clean that people unfamiliar with the technology sometimes suspect the numbers are overstated.

The second payoff is the ability of installers like Tebo to find help solving problems. If he has one, he can call Lallish.

“We’re looking right now at how different inhibitory chemicals can affect the MBRs. This kind of testing is something they can do better in a controlled environment than we can in the field,” Tebo says.

Since 2011, Tebo and his technicians have seen surges of various household chemicals coming through the systems they maintain. One of those substances is quaternary ammonia, which is used to control the growth of bacteria on surfaces and is a popular addition to domestic cleaning products. Another is triclosan, the antibiotic commonly used in household hand soaps and other products advertised as anti-germ.

“People are using quantities of these, and we cannot keep the biomass living,” Tebo says.

Because of the small pores in a reactor’s membrane, the treated water coming out is still clean, but the organic material on the other side of the membrane remains undigested until the bacterial population regrows.

In the field, his technicians check MBRs quarterly. They take a sample and that tells what the biology is at the moment, but it doesn’t reveal the entire sequence of changes in the system. And because it is an operating unit, Tebo can’t run experiments. That’s where the ERTC comes in.

“We try to do what we can to change the parameters and see what happens. We can introduce this with the influent and see what the effect is on the mixed liquor, the numbers and the visual indicators,” Lallish says.

Essentially, Tebo says, the ERTC people have the ability to watch what is happening in the reactor from moment to moment.

Now that the MBR is running, it has to be integrated into the course of instruction. In the spring, Lallish was working on guidelines for doing that. And he sees a lot of potential.

“It’s the same for me,” Tebo says. “When we have new people who want to come on board, we could send dealers down to take the course. And it would be good to avoid the headaches of having people in the field who don’t know how to operate these units.”