It’s trendy to talk about the need to have more students study what are called STEM subjects. That means science, technology, engineering and math. It’s to talk about the need to connect what students learn in classrooms to what happens in the world.

It turns out those pipes in your hands and that soil under your feet will do both of those educational jobs. Connecticut teacher Laura Poidomani saw this, too, as she worked to meet science instruction guidelines set out by the state of Connecticut.

Her use of wastewater systems for teaching sixth-graders earned a Presidential Innovation Award for Environmental Educators from the Environmental Protection Agency in 2017. She was the award recipient for the EPA’s Region 1 that covers Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. The awards recognize teachers who use hands-on approaches to educate students about the environment.

Pumper talked to Poidomani about her ideas and why her classroom features models of wastewater treatment systems.

Pumper: How did you decide to use septic systems as a tool for teaching?

Poidomani: Many years ago, the state of Connecticut adopted a rule requiring a common framework so students would have similar experiences no matter where they attended school, and one of those common experiences was experimenting with a variety of different soils. What kids did over the years seemed very random. Under the new guidelines, science is no longer a step-by-step process. Everything has to have a context, and that gave me the ability to link the state standard to septics. Now the kids have a purpose for what they learn because they have to design and construct a leaching field. They also have to study how septic tanks are designed so scum and sludge don’t clog their fields. This meets all the criteria for teaching STEM because they’re first using those skills to plan out the system on paper, and then they have to build the model they draw.

It sounds really easy to them, but when they start putting it together, they start respecting the process.

Pumper: And the use of wastewater also illustrates human impacts on the planet?

Poidomani: Right. The new standards also require us to look at human impacts on the environment. And septic systems have an impact on our local watershed and the greater watershed.

Pumper: How much experience have your students had with septic systems?

Poidomani: Every time I teach this course — and it’s only a three-month course — at least one or two kids have had experience with their parents letting their septic system overflow because they didn’t realize it was something they had to maintain.

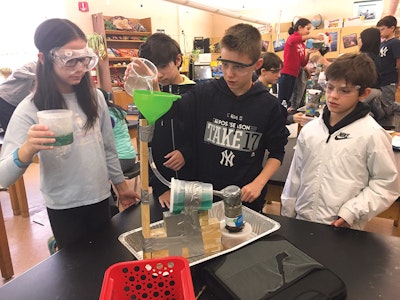

Pumper: What do your students use to build the model systems?

Poidomani: We use plastic tubing, three sizes of deli cups, funnels, screens and wood blocks to give structure. But we make sure they’re not using the screens to hold back sludge. The kids have to figure out what materials they can use to slow down the energy of the water. We use lots of water bottles. Unfortunately we also use a lot of duct tape and electrical tape because of the leaks. We talk about the difference between their models and the real world.

Pumper: What do you use to test the systems?

Poidomani: I make simulated wastewater out of whatever I can find that’s safe for the kids. That can mean some pencil shavings and minced toilet paper. I also use green food dye so it’s easy to see what goes through the leaching field.

The kids test six different soils. They have potting soil, topsoil from outside, clay, gravel, fine sand, and beach sand. Most kids realize quickly they want to use the clay and topsoil for slow drainage.

Pumper: What success do they have in cleaning the water?

Poidomani: It really depends on the kids. Last year I was running about 50 percent. Some years are better; some years are not. Part of it is the constraints we have to put on kids. A big one is that we can’t give them enough soil compared to what’s in a real septic system. Usually on the second try, kids are more successful. They’re really good at trapping the solids in the tank. It’s getting the green dye out of the water that is the challenge.

Pumper: What student insight has surprised you most?

Poidomani: I think their flexible thinking and willingness to take risks and try new ideas. Also their level of perseverance — the number of groups that will stay at it until their water comes out clean. Even the kids who don’t finish with clean water still walk away with a sense that they were able to do some of the work correctly. This takes away a lot of the academic barriers that kids have. Because it’s not content-focused but instead about building and collaboration, it seems all kids can be involved and engaged.

The other thing, too, I think it gives more respect to the profession. When we first start talking, the kids say, “Ew, who’d want to do that?” They learn there’s more to it — the chemistry involved and the planning.

Pumper: What is your community like?

Poidomani: We have many people who commute to New York City. It’s a pretty affluent area and a high-performing school district, but we also have children from all areas of life. We set the bar high for them, and kids generally reach that.

Pumper: Has this idea caught on with other teachers?

Poidomani: After I piloted the idea four to five years ago, now all sixth-grade teachers here use it for their STEM programs. It also helps kids to see that STEM doesn’t always have to involve a computer. I think kids better understand that technology is used to make life easier in different ways.